Don't Be a Hero (Seriously)

We glorify the founder grinding 80-hour weeks. The athlete who trains through pain. Then we copy the highlights without understanding the system behind them.

We are wired for heroes.

Not just in movies. In the office. On the field. In the gym. Everywhere.

We watch the founder who works 80-hour weeks and wills the company into existence. The athlete who trains through pain and crosses the finish line on pure grit. The executive who goes all-in on every decision, every meeting, every quarter.

We glorify the effort. The sacrifice. The grinding it out.

And then we try to copy the highlights. Without understanding the system behind them.

That's where most people go wrong.

The Story We Tell About Heroes

Stories are how humans make sense of the world. We've been telling hero stories since before writing existed. The structure is hardwired: ordinary person, extraordinary challenge, transformation through struggle.

We can't help but be drawn to it.

And it's useful. Heroes give us permission to believe we're capable of more. They show us what's possible. They raise the ceiling.

But there's a cost to hero worship that nobody talks about.

When we model heroic effort on a daily basis, we borrow against capacity we haven't built yet. We go all-in on a random Tuesday. We grind through when we should recover. We mistake output for progress and exhaustion for commitment.

The hero moment in every story is a peak. A singularity. The one time it all came together.

What you don't see is the 364 days of disciplined, boring, deliberate preparation that made it possible.

The hero moment looks effortless precisely because so much was conserved to produce it.

The Lao Tzu Problem

There's a line attributed to Lao Tzu that I keep coming back to:

"A leader is best when people barely know he exists. When his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves."

This is the opposite of the hero model.

The leader who shows up and crushes it every day, loudly, visibly, heroically, creates dependency. Their presence is the performance. When they're gone, the system collapses.

The leader who operates at minimum effective dose, doing what's necessary, building the conditions, and stepping back, creates something that outlasts them.

The goal isn't to be the hero of every scene. It's to be ready for the scene that actually matters.

What Minimum Effective Dose Actually Means

This is where I want to be precise, because MED gets misunderstood.

Minimum Effective Dose is not about doing less. It's not laziness with better branding.

It's the smallest stimulus that produces the desired adaptation. No more. No less.

In medicine, this concept is critical. Too little of a drug and nothing happens. Too much and you create toxicity. The dose that works is narrow, specific, and non-negotiable. The mechanism doesn't care about your intentions.

Training works the same way.

Your body adapts to stress by rebuilding stronger. But only if you give it the chance to rebuild. Overwhelm it before recovery is complete and you haven't trained harder. You've just created more damage to repair before you can train again.

The stimulus triggers the adaptation. The rest is where the adaptation actually happens.

MED means doing what's necessary, consistently, on a regular basis. So that when you need to go bigger, when it actually matters, you have something in the tank.

What This Looks Like In Practice

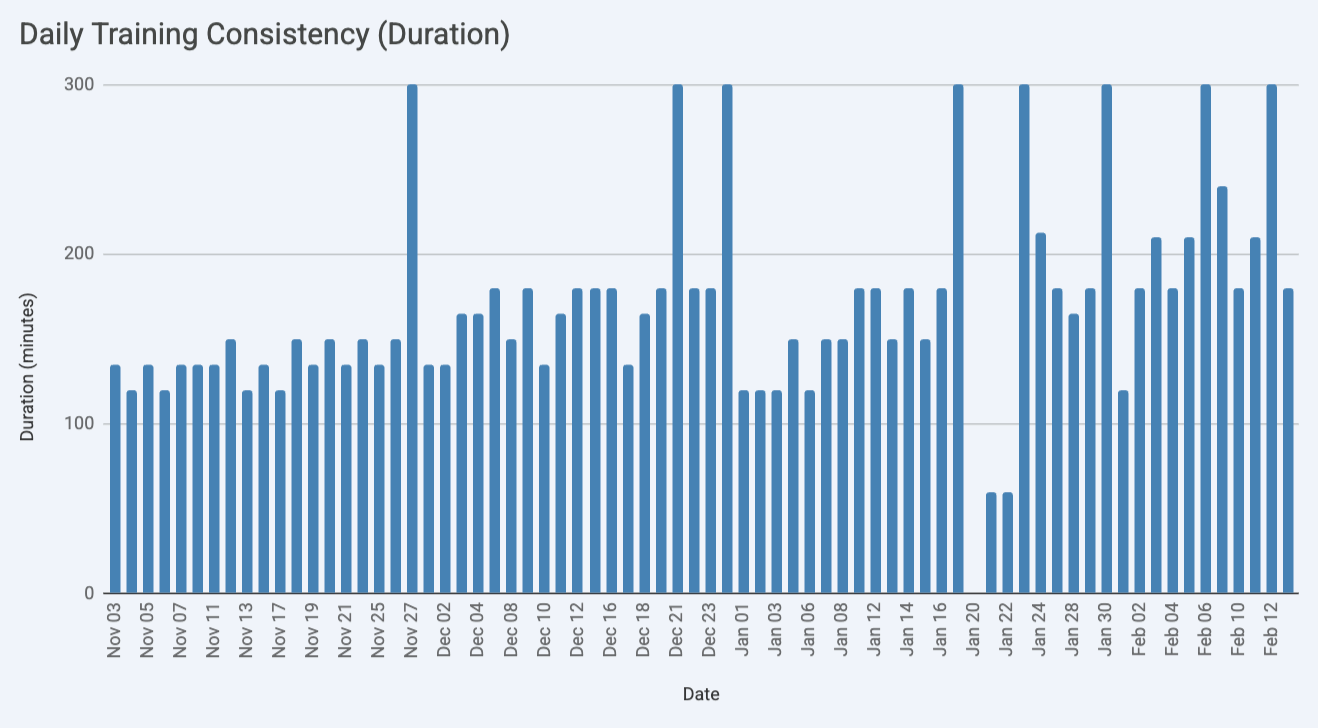

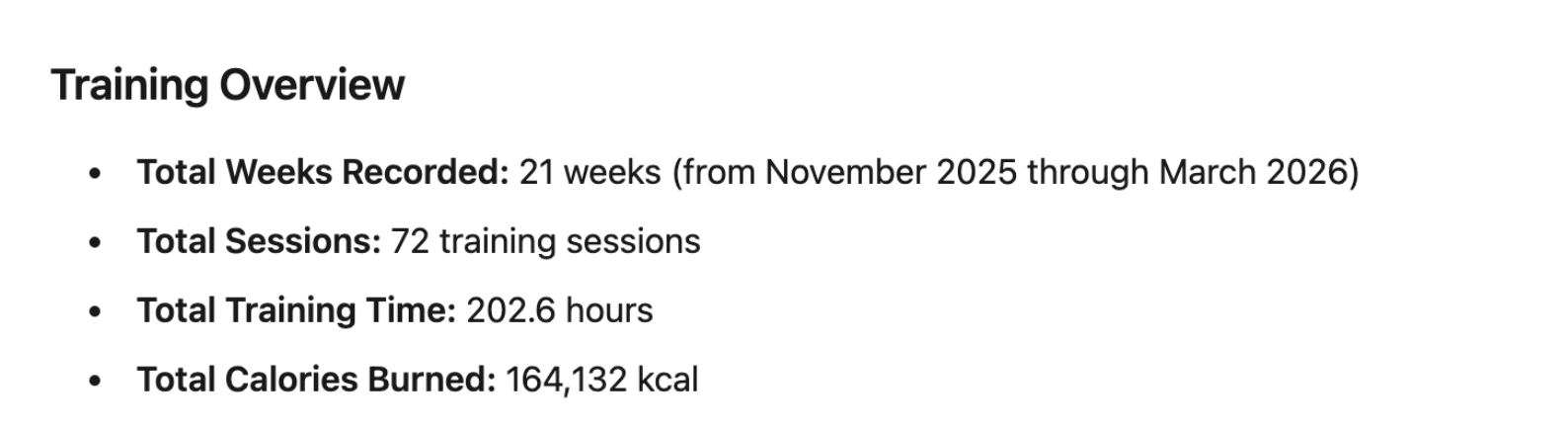

I'm 14 weeks into a base-building block for the Oregon Trail Gravel Grinder. Training 20 hours a week.

Almost none of those hours are hard.

Most of it is Zone 2. Conversational pace. Embarrassingly easy. I could hold a full conversation. I'm not suffering. I'm not proving anything.

I'm stressing my aerobic system just enough to force adaptation. Then recovering. Then stressing it again.

The fitness comes from the accumulation. Not from any single session.

And because I'm not shredding myself daily, I have capacity when I need it. If a hard effort is called for, I can deliver it. The tank isn't empty.

Compare that to my bathroom push-ups habit. Every time I leave the bathroom, I do 25 push-ups. No fanfare. No tracking app. No community accountability. Just a micro-habit anchored to something I'm already doing.

Six months in: thousands of push-ups I wouldn't have done otherwise. Noticeably stronger. Shoulder stability improved.

Not heroic. Consistent.

That consistency is what makes the hero moment possible when it shows up.

The Same Pattern Shows Up At Work

Three or four hours of deep, protected focus in the morning. Then meetings. Then lighter work in the afternoon.

Not 12-hour days. Not heroic output sessions. Just a deliberate dose of my best cognitive work at the time of day when I can actually produce it.

Because I'm not depleted by noon, I have capacity for the unexpected. That one conversation that matters. The critical decision that needs reflection.

The leader who runs at 110% every day has nothing left when the real thing arrives.

The leader who runs at 70%, deliberately and sustainably, can surge to 110% when it counts.

You Want To Be a Hero When It Matters

Not any given Sunday.

Any given Sunday, you should be doing the boring stuff. The Zone 2 miles. The push-ups off the bathroom. The protected focus block. The small, undramatic things that build the base.

Save the hero performance for the race. The pitch. The moment the team needs you. The decision that actually shapes the outcome.

Because heroism spent on ordinary days is heroism unavailable for the ones that aren't.

The best performers I know, in sport, in business, in life, are not grinding every day. They're building every day. And when the moment arrives, they're ready in a way that looks almost unfair.

People watch and say: how does he always come through when it matters? The answer is they've been conserving for exactly this.

They did the work. Nobody saw most of it. And when it was done, you'd almost say it happened by itself. That's the goal.

The Final Word

Pick one area (training, work, sleep, creative output) and reflect on the past week:

Am I running at hero pace every day, wondering why I'm depleted at the most important moments?

Or am I building consistently, conserving deliberately, and staying available for the moments that matter?

Every day is a choice.