Boring Enough to Win

The first time you do something, it's so hard. So complicated. The second time, it's marginally better. By the tenth time, you've stopped thinking about it. By the hundredth, it runs itself.

Patrick McCrannGiving high-growth founders an unfair advantage with community, peer capital & coachingJanuary 23, 2026

Bill Clinton kept handwritten index cards for nearly everyone he met.

By the early 1980s, there were around 10,000 of them. Each card held a name, personal context, the last interaction, and a prompt for the next one. Every night before bed, he'd pull the shoebox and write notes—thank-yous, birthdays, follow-ups. He did this for years.

Nothing about it looked like power. It looked like paperwork. Like homework.

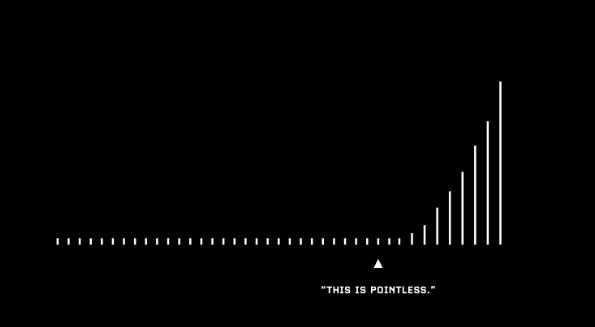

That's the trick with things that compound: what matters least in the moment matters most over time.

The days that matter don't feel like anything.

The first time you do something, it's so hard. So complicated. The second time, it's marginally better. By the tenth time, you've stopped thinking about it. By the hundredth, it runs itself.

That transition from deliberate to automatic is where most of the actual work happens. Not at the point of breakthrough. In the boring middle.

Early-stage founders usually don't lose because they lack effort or ideas. They lose because they're playing short games.

They spend two weeks building a newsletter template, send three issues, get distracted by a podcast opportunity, record five episodes, then pivot to Twitter threads when engagement drops. Each switch feels like progress. Each restart costs them six months of compounding they'll never get back.

The math is going to math with or without you. You have to decide what side of the equation you want to be on.

The games that matter are the ones where the longer you play, the better the odds get.

Writing is one of those games.

Relationships are one of those games.

Reputation is one of those games.

The more you write, the more chances you create for connection. The longer you write, the longer the tail of opportunity. That's why founder-led media works. Consistency builds a landing pad over time.

Clinton's system wasn't sophisticated. A handwritten 3×5 card. But he did it for everyone. Oxford classmates, Arkansas contacts, random people at events. By the time he ran for president, he had an insane and active network built on points of contact and value delivered. People remember his charisma, but it was how he operationalized it contributed to his success. 30 minutes a day for 15 years.

There's nothing remarkable about writing a few notes a day. Until you do it for 20 years. Then it looks like genius.

If this feels abstract, use your body to understand it. Running is a good example.

Running is simple. Minimal equipment. Clear rules. Real upside. But running has a real problem.

The first run is miserable. Your lungs burn. Your legs feel heavy. Every corner is an exit ramp. You spend the entire time negotiating with yourself about whether to quit.

By the third run, your body iht still hate it, but your brain has a reference point. You know what to expect. The chaos becomes predictable.

By the tenth run, you've stopped deliberating. Shoes by the door, same route, same time. Opting in becomes the default. Opting out stops being an option.

Nothing about running gets easier. Consistency just makes it less something that you do and more someone you are. It becomes your identity.

Coaches call this tactical boredom.

At a certain level of practice, progress stops coming from intensity and starts coming from absorption. You don't hype yourself up, you tune in. The repetition becomes the work. Time moves faster because your attention narrows.

That's what long-term competence actually feels like.

Watch a pro athlete train and you'll mostly see boring stuff: single-leg balance work, hip stability drills, band exercises. Nothing explosive. Nothing sexy. Just the maintenance work that keeps them in the game for a decade.

To be clear, the training is not any less hard. It's just cheaper.

Consistency doesn't make hard things easy. It makes them cheap. Same effort, less friction. Same output, less drain. The energy you used to burn on decisions gets reinvested elsewhere.

"Most people need consistency more than they need intensity. Intensity makes a good story. Consistency makes progress." - James Clear

The mistake most people make is overestimating the importance of one defining moment and underestimating the value of making small improvements on a daily basis.

You can't compound a big day. You can only compound something you're willing to repeat.

So the real work isn't finding the perfect tactic.

It's deciding what's worth experimenting with, what's worth repeating, and what you're willing to make boring.

The right model is experiment → repeat → commit. You try something small.

You run it enough times to learn. And if the signal is there, you stay with it.

Even things that are good for you are hard the first time.

What are you willing to stay with long enough for it to work?